Good links all related to football strategy, though we begin with a video of Gus Malzahn’s Auburn O, via Offensive Musings:

– Defending the bunch. If a defense plays a lot of man coverage, you can bet that the offense (if they have any sense, anyway) will quickly start using “bunch” or “compressed” formations. Anyone who has ever played backyard football can give the answer: it’s much easier to get open if your defender can get “screened” by congestion of some sort — either your teammate running a “legal screen” (versus, ahem, an illegal pick which no one ever does, right?) or even some cluster of receivers and defenders. Defenses, not to outdone by such offensive wizardry, have responses, summed up well in posts by RUNCODHIT and Blitzology.

Unsurprisingly, discipline is a key factor. Blitzology covers some mechanics, while RUNCODHIT adds some background:

[Y]ou can’t run press-man on both WRs[;] alignment won’t allow you to. Also, to run straight man against reduced splits is suicide. The offense will pick you off and open-up a WR to the inside or outside. Because of this threat, defenses have to stay in pure-zone or combo-man coverage.

And,

versus the run 3-way [coverage] places the [strong safety] in a position to force the ball inside. The corner is assigned play-pass responsibility, and the [free-safety] is a flat-foot read player . . . . Against the pass the . . . [strong safety] has the first man to the flat. If no one attacks it, he sinks under the first WR outside. The corner[back] has the first deep route outside — he is going to [back]pedal on the pass and read the WRs. The FS has the first man deep inside. His technique is essentially the same as the corners’. If a deep receiver does not show in or out, then they play a “zone it” technique and help their partner.

Bonus: Check out RUNCODHIT on “Pattern Reading vs. Zone Dropping” and Blitzology’s series on attacking BOB or Big on Big pass protection. (I’ve described the principles of this protection here.) Series parts one, two, three, and BOB vs. the 3-4 defense.

– Think you have what it takes to be an NFL guy? Check out this Slate article on the work ethic of NFL coaches. The answer — it’s about managing people, as much as it is about strategizing and ideas:

What exactly does a head coach do for 23 hours every day? . . . Imagine telling George Halas that he should have worked 20-hour days. He would have laughed you out of his office, then gone back to inventing the T-formation. No matter how many variations on the spread offense you come up with, it’s still the spread offense, not Fermat’s Last Theorem. . . . The guy with the biggest whistle has a fleet of coordinators and position coaches that handle all the grunt work, from conditioning to game-planning to skill-training. . . . Instead, the coach functions as a sort of CEO, coordinating large-scale strategic planning while ensuring all members of his organization perform competently. Viewed through that lens, this endemic insomnia shouldn’t come as a surprise. After all, CEOs fetishize waking up early just as much as football coaches. . . .

– Screenery strategery. If you’re going to spread the ball out or throw the ball at all, day one is usually spent working on the basics of passing: timing, quarterback drops, rhythm, catching, and the basic routes. Day two, however, goes to screens, those little gadget plays that, particularly at the lower levels, make being a pass first team really worth it. These impressive little suckers manage a quite impressive trifecta: (1) they are easy to complete (and maybe should be thought of as runs rather than passes), which can build your quarterback’s confidence and allow you to get the ball to your playmakers in space; (2) they are often your best weapon against aggressive, blitzing defenses, which can otherwise overwhelm young players just learning how to throw the ball efficiently; and (3) unlike a lot of passing-related concepts, these make heavy use of misdirection, that great equalizer between teams of greater and lesser talent.

In that vein, two great primers out there are Mike Emendorfer’s UW-Platteville screen presentation and this recent post from Brophy’s blog.

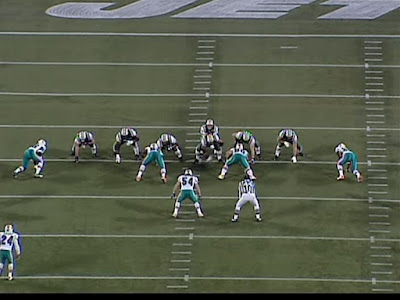

– Football and math, oh my. Good post on the basics of “football math” — i.e. who and where do you attack. Here’s a test: Where would you attack in these two situations?

Bonus: See clinic notes here and here from DACOACHMO.

– No surprise there: Bill Walsh gets it. Brian from Advanced NFL Stats quotes one of Bill Walsh’s best nuggets on playcalling:

We know that if they don’t blitz one down, they’re going to blitz the next down. Automatically. When you get down in there, every other play. They’ll seldom blitz twice in a row, but they’ll blitz every other down. If we go a series where there haven’t been blitzes on the first two downs, here comes the safety blitz on third down.

Brian has more on the theory behind Walsh’s practical wisdom, and I discussed the subject of randomizing playcalls a few years back:

In Edgar Allan Poe’s story The Purloined Letter, a character recounts a story of a young man who excels at game called “odds and evens,” known somewhat more popularly now as “matching pennies.” The game is a two-strategy version of rock-paper-scissors: Each player secretly turns their coin to heads or tails and then both reveal their choices simultaneously. If the pennies match (both heads or both tails) then one player gets a dollar; if they do not then the other gets the dollar. As told in the story, the young man quickly sizes up his opponents, gains a psychological advantage, and amasses a fortune by outguessing his opponents.

I suppose all playcallers think themselves like the young man, but most are probably more similar to the suckers. But here’s the rub: The suckers could nullify the young man’s psychological advantage. How?

By choosing randomly. If the suckers put no thought into whether they chose heads or tails, they would do better than if they tried their best to out-think him. They would break even — a fantastic result against the world’s greatest matching pennies player, an unnatural genius who, according to the story, would go through lengthy Sherlock Holmsian deductions to determine if his opponent would choose heads or tails, and of course almost always guessed correctly.

This is a breath-taking result: you can nullify anyone’s advantage by picking randomly. But it is also scary — would I be better off picking my plays entirely randomly?